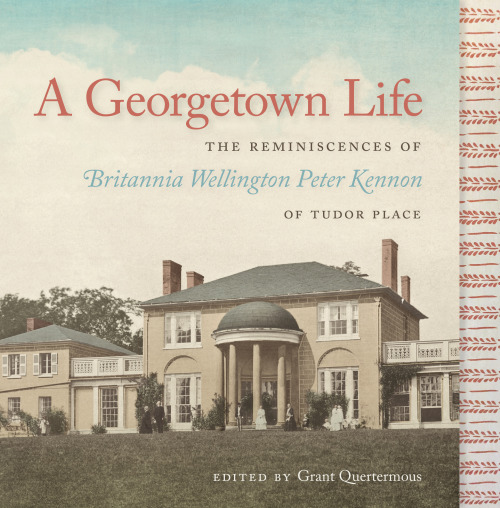

A Georgetown Life: The Reminiscences of Britannia Wellington Peter Kennon of Tudor Place

As a Georgetown resident for nearly a century, Britannia Wellington Peter Kennon (1815 – 1911) was close to the key political events of her time. Born into the prominent Peter family, Kennon came into contact with many notable historical figures of the day, often entertaining them at Tudor Place, her home for over 60 years. Now available to the public for the first time, the record of her experiences offers a unique insight into nineteenth century American history. Lavishly illustrated, the book includes an exact transcription of the original Reminiscences, annotations with details about the people, places, and events noted in the text; a biographical essay; and an essay on the creation of the original document. Read on for a Q&A with editor Grant Quertermous, former curator of Tudor Place.

Who was Britannia Kennon?

A great-granddaughter of Martha Washington, Britannia Wellington Peter Kennon (1815-1911) was a truly fascinating but fairly unknown historical figure who lived for all but a few years of her life at Tudor Place, the Peter family estate in the Georgetown neighborhood of Washington, D.C. Britannia embraced the Custis-Peter family’s historic lineage and role in American history and instilled that same sense of family pride in several subsequent generations of her descendants. An early member of both the DAR and the Colonial Dames, Britannia conducted her daily correspondence at Martha Washington’s writing table, a piece of furniture her mother received as a bequest in 1802. Britannia was also the owner of a significant collection of manuscripts and objects that her parents acquired following Martha Washington’s death. Beginning in the 1890s, Britannia’s grandchildren prompted her to recall anecdotes and information about the people she had met, such as Lafayette or President Andrew Jackson, as well as her experiences as a southerner during the Civil War. The notes from these interviews were preserved by her grandson, Armistead Peter Jr., and are now found in the Tudor Place archives.

What will this book add to our understanding of 19th century America?

The Reminiscences provides an unparalleled look at daily life in 19th century Georgetown and greater Washington, D.C. in the four decades before and immediately following the Civil War through the eyes of one woman who experienced it firsthand. To her grandchildren, Britannia recalled the dancing lessons she took with the daughter of neighbor and Vice President John C. Calhoun as well as her memories of meeting well-known figures in American history ranging from Daniel Webster to Elizabeth Schuyler Hamilton, the widow of Alexander Hamilton whom she befriended in the 1850s. Britannia also passed along information about George and Martha Washington that Martha Custis Peter had recounted to her—such as how President Washington would often lodge with the Peters at their earlier K Street residence when he came to survey the progress of construction on the Federal City. Britannia also provides an insight into the complicated and complex relationships forged between master and slave, recalling by name the many individuals who labored at Tudor Place and other family properties during her childhood and later during her widowhood prior to the emancipation of slavery.

What insight did working as curator of Tudor Place give you into the people who lived there?

It has certainly shown me that regardless of how much information we have about the Peter family’s occupation of Tudor Place—the archives have more than 250,000 manuscript pages and the museum collection consists of nearly 18,000 objects—we’re not always going to be able to know everything. And that’s both an endless source of frustration and fascination. For example, while I know exactly where in the house Britannia Kennon was born, the room in which she was married, the room in which she gave birth to her daughter, and even the room in which she died, I don’t know exactly what happened the day that her slaves were emancipated or her reaction to freeing this captive labor force. As a curator, I always point out that Tudor Place was first and foremost a family’s home. Six generations of the same family lived within the house—many were born and even died there. The objects in the collection and documents in the archives help us to better tell the family’s stories as well as the stories of those people who aren’t always as visible in the historical record but play an equally important part of history—those who labored there for the family, both the enslaved and the later domestic servants, many of whom were immigrants. To so many people, history is just a series of names and dates. Yet it’s so much more than that.